Mr. Luke & Lady Midnight.

Mr. Luke & Lady Midnight.

Breeds of poultry are divided into four categories, breeds, varieties, types, and classes. Breed, color of plumage, type of comb, and size identify the different varieties of chickens.

Breed- A group of related birds which breed true to specific, repeated, given traits which are then used to identify the breed.

Varieties-The breeds of chickens and other fowl are then divided into varieties based on certain traits such as the color of their plumage (feathers), comb type, or other specific traits.

Type-Refers to the purpose which the poultry are bred for such as, egg-type and meat-type.

Class-In the U.S. there are four classes generally used which are Mediterranean, American, English, and Asiatic.

Most chickens used for egg and meat production are produced by cross-mating, breed crossing, or inbreeding.

Does the rooster or the hen determine the sex of baby chicks?

The hen (female) determines the sex of baby chicks. Female chickens only have one sex chromosome while the male chicken has two sex chromosomes. The chromosomes carry genetic traits which are passed on to the offspring (Gillespie,1983).

See more about breeding chickens below.

Breed- A group of related birds which breed true to specific, repeated, given traits which are then used to identify the breed.

Varieties-The breeds of chickens and other fowl are then divided into varieties based on certain traits such as the color of their plumage (feathers), comb type, or other specific traits.

Type-Refers to the purpose which the poultry are bred for such as, egg-type and meat-type.

Class-In the U.S. there are four classes generally used which are Mediterranean, American, English, and Asiatic.

Most chickens used for egg and meat production are produced by cross-mating, breed crossing, or inbreeding.

- Cross-mating-Mating two or more strains within the same breed.

- Breed crossing-Mating different breeds to get desired traits.

- Inbred chickens- Mating the inbred lines to get the desired traits.

Does the rooster or the hen determine the sex of baby chicks?

The hen (female) determines the sex of baby chicks. Female chickens only have one sex chromosome while the male chicken has two sex chromosomes. The chromosomes carry genetic traits which are passed on to the offspring (Gillespie,1983).

See more about breeding chickens below.

Choosing a Rooster for Breeding Purposes

Larry the Rooster. Sired by Rhode Island Red Rooster and Cochin hen.

Larry the Rooster. Sired by Rhode Island Red Rooster and Cochin hen.

When preparing your breeding program selecting the right rooster is an essential. Aggressive roosters tend to have higher testosterone levels which results in more fertilized eggs. Roosters should be selected from good, strong, healthy breeding stock with the desired physical attributes. Studies show in natural selection, hens will select their own mate and are more likely to choose a rooster with healthy genes. Hens which are allowed to select their own mate are less likely to reject the sperm. Studies show, "copulations per se do not necessarily result from the choice of a female, and may be forced by the male (Pizzari et al., 2002). Such events do not reflect reproduction success (Bilcik and Estevez, 2005) because females can eject sperm by contractions of the cloacae. This mechanism enables females to get rid of sperm of males they do not favor (cryptic female choice, Birkhead and Møller, 1992; Pizzari and Birkhead, 2000)". (I. Tiemann, G. Rehkämper, 2009).

In artificial selection it is important to consider carefully which genes you want replicated in your baby chicks such as color of feathers, comb type, leg color, and even posture. It is best to select a rooster who is not closely blood related and of the same breed as your hens to maintain the breed standard. Make sure your breeder rooster is in good health, has an undamaged comb, has bright eyes, leg scales which do not lift off from the legs, no pasty residue on the vent area, does not limp, has no sores or injuries on the bottom of their feet or anywhere on their body. It is a good idea to have both your breeding rooster and hens checked out by a local livestock and poultry veterinarian before breeding them.

" A poor sexual mate choice will lead to offspring that might not withstand natural selection, whereas a good mate choice results in offspring with a genetic predisposition to handle natural selection on a big scale (I. Tiemann, G. Rehkämper, 2009)..

In artificial selection it is important to consider carefully which genes you want replicated in your baby chicks such as color of feathers, comb type, leg color, and even posture. It is best to select a rooster who is not closely blood related and of the same breed as your hens to maintain the breed standard. Make sure your breeder rooster is in good health, has an undamaged comb, has bright eyes, leg scales which do not lift off from the legs, no pasty residue on the vent area, does not limp, has no sores or injuries on the bottom of their feet or anywhere on their body. It is a good idea to have both your breeding rooster and hens checked out by a local livestock and poultry veterinarian before breeding them.

" A poor sexual mate choice will lead to offspring that might not withstand natural selection, whereas a good mate choice results in offspring with a genetic predisposition to handle natural selection on a big scale (I. Tiemann, G. Rehkämper, 2009)..

Selective Breeding

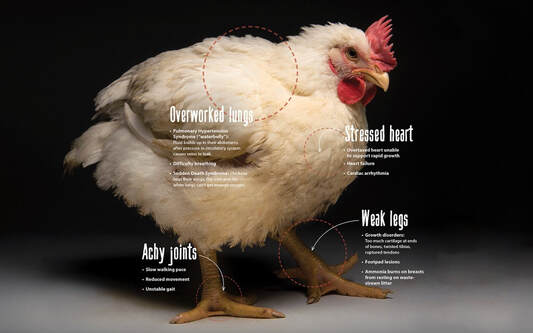

A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. (2015)

A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. (2015)

Selective breeding can be used to reproduce certain desired characteristics in the chickens offspring. When using selective breeding care should be taken to breed birds of the same breed type to keep the breed standard. Size should be considered when breed crossing chickens to prevent genetic defects and serious health issues. Breeding a standard size bird with a smaller breed such as a bantam or silkie may cause birth defects which can be fatal. For example, the inherited skull size may end up being the size of the smaller bird while the brain size of the larger bird may be inherited which can cause the brain to put pressure on the smaller skull and eventually as the inherited larger brain outgrows the smaller size of the inherited skull it will put significant pressure and separation of the skull which can cause birds to become uncoordinated and death. Growth of vital organs could be impaired by breeding birds of different sizes as well. For example, breeding a standard size breed with a bantam breed could result in bantam size vital organs and a standard size bird which would leave the vital organs incapable of sustaining a large bird.

Commercial broiler birds are an example of poor selective breeding.

Broiler birds were bred for fast weight gain characteristics and as a result the birds grow extremely fast and gain an excessive amount of weight which is too heavy for the birds legs bone structure which will collapse under the extra weight. "The type of chicken commonly used today grows at a rate 300% faster than those in 1960. They reach heavier weights than in years past but in significantly less time. In fact, according to researchers at the University of Arkansas, these chickens grow at a rate equivalent to a two-month-old human baby weighing 660 pounds!* Barely able to move at just a few weeks old, these overgrown “Cornish Cross” breed birds typically spend their lives warehoused in overcrowded massive sheds where dim, constant lighting keeps them continuously eating—virtually all they’re able to do—in a constant pursuit of higher efficiency and productivity. Today’s fast growing birds are so heavy and weak that they often collapse or struggle to stay standing. All of this pushes their bodies and immune systems to the brink. Farms routinely feed them preventative antibiotics, creating a vicious cycle that allows them to perpetuate substandard conditions and raising significant questions about the implications for human health. These are the chickens that make their way to America’s dinner plates every day" (A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. 2015. https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/chix_white_paper_nov2015_lores.pdf).

Commercial broiler birds are an example of poor selective breeding.

Broiler birds were bred for fast weight gain characteristics and as a result the birds grow extremely fast and gain an excessive amount of weight which is too heavy for the birds legs bone structure which will collapse under the extra weight. "The type of chicken commonly used today grows at a rate 300% faster than those in 1960. They reach heavier weights than in years past but in significantly less time. In fact, according to researchers at the University of Arkansas, these chickens grow at a rate equivalent to a two-month-old human baby weighing 660 pounds!* Barely able to move at just a few weeks old, these overgrown “Cornish Cross” breed birds typically spend their lives warehoused in overcrowded massive sheds where dim, constant lighting keeps them continuously eating—virtually all they’re able to do—in a constant pursuit of higher efficiency and productivity. Today’s fast growing birds are so heavy and weak that they often collapse or struggle to stay standing. All of this pushes their bodies and immune systems to the brink. Farms routinely feed them preventative antibiotics, creating a vicious cycle that allows them to perpetuate substandard conditions and raising significant questions about the implications for human health. These are the chickens that make their way to America’s dinner plates every day" (A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. 2015. https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/chix_white_paper_nov2015_lores.pdf).

More About Chicken Breeds & Breeding |

- Gillespie, James R. . Modern LIvestock & Poultry Production. 2nd ed., Delmar Publishers Inc., 1983, p. 92, 497-498.

- I. Tiemann, G. Rehkämper, Effect of artificial selection on female choice among domesticated chickens Gallus gallus f.d., Poultry Science, Volume 88, Issue 9, September 2009, Pages 1948–1954, https://doi.org/10.3382/ps.2008-00250

- A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. (2015). Retrieved 1 December 2019, from https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/chix_white_paper_nov2015_lores.pdf

- A Growing Problem Selective Breeding in the Chicken Industry: The Case for Slower growth. (2015). Retrieved 1 December 2019, from https://www.aspca.org/sites/default/files/chix_white_paper_nov2015_lores.pdf